I am putting this post here in the hope that people looking for the print version of Yoon-Suin will find this entry after searching. Sadly, Yoon-Suin is no longer available from lulu, apparently because they cannot now print landscape books which are longer than 250 pages.

This is annoying, to put it mildly, but it does provide the opportunity to finally put out a revised edition of the book, perhaps with extra material, at some point this year. (And not with lulu, who I won't be using again.) Watch this space for details.

The book is still available on PDF from Payhip, drivethrurpg.com and the Noisms Games website.

Creator of Yoon-Suin and other materials. Propounding my half-baked ideas on role playing games. Jotting down and elaborating on ideas for campaigns, missions and adventures. Talking about general industry-related matters. Putting a new twist on gaming.

Sunday, 31 May 2020

Wednesday, 27 May 2020

Are You Experienced

Comments on recent posts led me to revisit the 2nd edition AD&D DMG (God help me) and its Chapter 8 - on "Experience".

These rules are easily, and fairly, criticised on a number of grounds. Foremost among these criticisms is the rules' arbitrariness, encompassed in the notion that "the number of points given a player for a game session is a signal of how well the DM thinks the player did in the game". In other words, they're a method for rewarding whatever the individual DM's conception of "good role playing" entails. Favouritism, inconsistency, mistakes, unfairness, resentment - what could possibly go wrong? The worst element of all this is the idea that experience points should be awarded for meta concerns such as whether a player got involved properly, encouraged others, interfered too much, or acted like a "rules lawyer". Why it is the DM's business to passive-aggressively police the behaviour of the players through XP awards rather than just taking them to one side and saying, "Stop being an arsehole" is beyond me. Almost as bad is the idea of getting XP for achieving "story goals" - a rule that positively incentivises the absolute worst thing about bad gaming: railroading.

The beauty of XP for treasure is not just that it is simple but that it also tells you what "good role playing" is - getting treasure and surviving. It is what Ron Edwards might have called "coherent". This might not be to all tastes, but those other tastes are served by other games.

The 2nd edition way of awarding experience points was always unworkable in practice except in limited circumstances (like an adult DM with a group of youngish children), and it is mostly a historical curiosity now - or at least it should be. But it's possible that there is one bit worth rescuing. This is the class awards. Briefly summarised, these are:

These rules are easily, and fairly, criticised on a number of grounds. Foremost among these criticisms is the rules' arbitrariness, encompassed in the notion that "the number of points given a player for a game session is a signal of how well the DM thinks the player did in the game". In other words, they're a method for rewarding whatever the individual DM's conception of "good role playing" entails. Favouritism, inconsistency, mistakes, unfairness, resentment - what could possibly go wrong? The worst element of all this is the idea that experience points should be awarded for meta concerns such as whether a player got involved properly, encouraged others, interfered too much, or acted like a "rules lawyer". Why it is the DM's business to passive-aggressively police the behaviour of the players through XP awards rather than just taking them to one side and saying, "Stop being an arsehole" is beyond me. Almost as bad is the idea of getting XP for achieving "story goals" - a rule that positively incentivises the absolute worst thing about bad gaming: railroading.

The beauty of XP for treasure is not just that it is simple but that it also tells you what "good role playing" is - getting treasure and surviving. It is what Ron Edwards might have called "coherent". This might not be to all tastes, but those other tastes are served by other games.

The 2nd edition way of awarding experience points was always unworkable in practice except in limited circumstances (like an adult DM with a group of youngish children), and it is mostly a historical curiosity now - or at least it should be. But it's possible that there is one bit worth rescuing. This is the class awards. Briefly summarised, these are:

- Fighters get XP for "defeating" enemies

- Priests get XP for successfully using their powers, casting spells to further their ethos, and making stuff

- Wizards get XP for casting spells to overcome "foes or problems", researching things and making stuff

- Rogues get XP for using their special abilities and, er, treasure

This is at least worth playing around with as the sole method of awarding XP where the desire is to get away from the "PCs as rogues" motif that is at the heart of what the OSR is all about. It is coherent in a different way, in that it at least attempts to link XP with what the various classes are supposed to be for.

The immediate consequence that suggests itself is that this would incentivise slavish and unthinking pursuit of what you might call class priorities: the fighter wants to kill everything; the magic-user is constantly trying to come up with magical solutions to solve problems; the thief is just after treasure. This could have its charms. One could imagine all sorts of amusing and interesting consequences flowing from having an adventuring party whose priorities are fundamentally orthogonal and occasionally even directly at odds with each other. Although one could also imagine priorities being so different that it becomes difficult to reconcile them.

Another is the mid-game. In my experience as the players begin to amass cash they tend to use it to make investments (in 99% of cases this is building a pub; in 1% it is fortifications). If most PCs don't have a massive interesting in getting treasure in order to advance, are they going to be as wealthy as they go up in levels? What does a fighter do whose only real goal is to fight? Or a wizard whose only real goal is to use magic and research it? The answer: much more adventuring, but for other aims than financial.

How this would work in practice remains to be seen: as usual, have at it in the comments.

Tuesday, 26 May 2020

Back of a Beermat Rules for Tolkienesque BECMI or BX Magic

If I were to run a game in Middle-Earth - Blue Wizards or otherwise - I would probably use Basic Holmes/Moldvay/Mentzer D&D, and most likely the Rules Cyclopedia. This is largely because I am old and lazy and set in my ways. I have MERP and played it a lot as a youngster, but it is complicated and would involve re-learning. I have The One Ring RPG and I am sure it is great, but I would have to learn it from scratch. I am convinced that the best system for Middle-Earth gaming would actually be a variant of Pendragon. But this would involve work to adapt the Pendragon rules. Realistically, then, the system with which I am most familiar is the one to go with, and that's Basic D&D.

The immediate problem with this is magic. As people who write about RPGs set in Middle-Earth never tire of emphasising, Tolkien's magic is nothing like D&D magic. It is rare and mysterious, where D&D magic is relatively common and systematic. It also has an air of danger about it for the caster - there is a strong sense that magic is intrinsically corrupting, and certainly not to be dabbled with.

But one wouldn't want to overcomplicate the blissful simplicity of Basic D&D with new systems. And at the same time one would, I think, want PCs to have access to magic of various kinds. I would simply introduce some restrictions:

The last of these is hardest to systematise, but perhaps it is better that way - it would give the DM room to get creative.

The immediate problem with this is magic. As people who write about RPGs set in Middle-Earth never tire of emphasising, Tolkien's magic is nothing like D&D magic. It is rare and mysterious, where D&D magic is relatively common and systematic. It also has an air of danger about it for the caster - there is a strong sense that magic is intrinsically corrupting, and certainly not to be dabbled with.

But one wouldn't want to overcomplicate the blissful simplicity of Basic D&D with new systems. And at the same time one would, I think, want PCs to have access to magic of various kinds. I would simply introduce some restrictions:

- PCs cannot be magic-users - although they can be clerics, druids or elves and use magic accordingly

- There are magic-users, but becoming one involves becoming corrupted, and the PCs ought to be the Goodies in a Middle-Earth game

- Whenever clerics, druids or elves use magic, there is a chance that this is noticed by servants of Morgoth, increasing with the level of the spell cast - and there would be a table for determining which such servants came to investigate (there was something along these lines in MERP)

- There are magic items, but their use is always associated with some risk of becoming enthralled to Sauron, one of the Blue Wizards, the former owner, some malevolent entity, etc. (perhaps a 1% daily risk of becoming 'turned' and taken over by the DM as an NPC)

The last of these is hardest to systematise, but perhaps it is better that way - it would give the DM room to get creative.

Friday, 22 May 2020

More Thoughts on Blue Wizards

I have no idea what Tolkien had in mind for the geography of Rhun and the peoples within it. But it seems to me that, while one shouldn't think of Middle Earth as being too closely paralleled with the real world, there is a case to be made that its character is roughly akin to the Eurasian steppe this side of the Urals - more specifically the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea (with the Sea of Rhun here being a bit like the Black Sea).

There are a few reasons why I think there are good reasons for drawing some parallels between Middle Earth and the real world, here, again with the proviso in mind that we're not just making one an allegory for the other:

There are a few reasons why I think there are good reasons for drawing some parallels between Middle Earth and the real world, here, again with the proviso in mind that we're not just making one an allegory for the other:

- We are told in The Silmarillion that beyond the Sea of Rhun is the Sea of Helcar, another big inland sea. Helcar would seem to be rather like the Caspian to Rhun's Black Sea. We're also told that beyond that there is a range of mountains called the Red Mountains, which seem to me like they ought to be the Caucasus/Urals.

- Rhun is inhabited by Easterlings, who are apparently nomadic or at least semi-nomadic. This implies both a steppe landscape and also cultures something like the Cossacks, Alans, Huns, Magyars, Bulgars, Scythians and other tribes who circulated on the Pontic Steppe at various stages of its history.

- The Numenoreans apparently also had colonies around the Sea of Rhun, which suggests to me something along the lines of the Greek colonies on the Crimea, which culminated in the 'Greco-Scythian' Bosporan Kingdom. You can imagine Numenoreans still living in these colonies in the Third Age, perhaps with 'Numenoreanised' Easterling populations as well.

- Humans purportedly came from this area originally and this seems to chime, in my mind, with the Pontic Steppe being the original home of proto-Indo-European speakers in the real world.

- Well, it looks flat, doesn't it?

A setting suggests itself in which there is a huge steppe populated by many wandering nomadic (or semi-nomadic, based in sichs) tribes with highly distinctive cultures and languages - perhaps hunting vast herds of the Kine of Araw. But there are also towns proper, home to fallen or debased Numenoreans and their 'Numenoreanised' populations. And there are perhaps, too, the ruins, tombs and monuments of a much more extensive Numenorean realm, now mostly forgotten.

But there are other ingredients too. The agents of Saruman and Sauron are abroad (such a Tolkienesque word), searching for clues about the Blue Wizards and spreading mischief. There are dwarfs living in the hills around the Sea itself - indeed, it is implied that a majority of the dwarves of Middle Earth are actually living in Rhun. Elves too - mysterious and forbidding Avari deep in those forests on the north-east shore of the Sea. And the odd dragon, natch.

What of the Blue Wizards themselves? If we can think of Rhun as the Pontic Steppe, we can think of the Wizards as being beyond it - in Khwarazmia, maybe, or Transoxania - but perhaps that would be to give the game away. In any event, we can be sure that they left "secret cults and 'magic' traditions" behind them as they passed through the steppes of Rhun.

Monday, 18 May 2020

Dreaming is Free: Towards an 'In Search of the Blue Wizards' Campaign

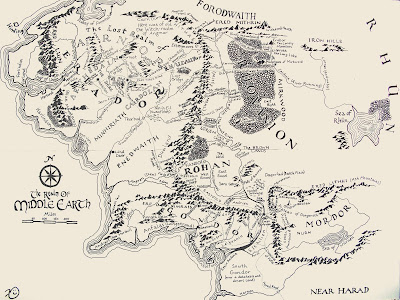

Is it possible to look at the map above and not feel a wave of nostalgia washing over you like a tsunami?

Anyway. The Blue Wizards. Tolkien had different conceptions of them through his career. The version I prefer is from his letter of 14th October 1958 to Rhona Beare:

I really do not know anything clearly about the other two [wizards] – since they do not concern the history of the N[orth].W[est]. I think they went as emissaries to distant regions, East and South, far out of Númenórean range: missionaries to 'enemy-occupied' lands, as it were. What success they had I do not know; but I fear that they failed, as Saruman did, though doubtless in different ways; and I suspect they were founders or beginners of secret cults and 'magic' traditions that outlasted the fall of Sauron.

There is so much in that small paragraph: distant regions, vagueness about success or failure, how the wizards might have failed in 'different ways' to Saruman, what secret cults or magical traditions they founded and more besides. Plenty for a DM to get his teeth into, anyway.

I imagine the campaign covering the area beyond Mirkwood, encompassing the Iron Hills, the Sea of Rhun, and Rhun itself - and beyond. Ostensibly, the PCs would be going in search of the Blue Wizards, perhaps under the command or instigation of Gandalf or Elrond, but there would of course be much more to the campaign than this. There would be Easterling tribes of myriad types, some nomadic, some living in walled towns. There would be degenerate Numenoreans, perhaps something like the black Numenoreans of the South - the remnants of colonies from the Second Age - or undead ones (or only the ruins of the civilization they built). There would be agents of both Saruman and Sauron going hither and thither across the land, trying to thwart the PCs and find the Blue Wizards for themselves. There would be roving orcs and other of Morgoth's creations. But there would be elves and dwarves too, perhaps of unusual Avari types in respect of the elves, and perhaps of a more primal or wild nature in the case of the dwarves. And, naturally, there would be these "secret cults and 'magic' traditions" that Tolkien so tantalises us with.

The campaign would be a sandbox, but one which I think of as a purposive hexcrawl. There would be clues scattered across the map as to the Blue Wizards' whereabouts. But many of these would have to be red herrings or diversions, and of course the PCs might well be distracted by other things too, not the least of which being rival groups of Saruman and Sauron's servants. Crucial in all of this would be to start the PCs off already having several avenues to explore, and taking things from there - giving them options, and then seeing what pre-arranged clues are subsequently uncovered.

Friday, 15 May 2020

The Adventurer-Dense to Adventurer-Sparse Spectrum: Vance to Tolkien

In Jack Vance's fiction, adventurers tend to be commonplace. (Indeed, in some respects almost everybody in Vance's novels are adventurers, because you rarely meet anybody who isn't vigorously pursuing some personal private quest, vendetta, mission or task of some kind.) Think of the various magicians and their rivalries in the "Dying Earth" stories; or the entire global economy of Tschai and its reliance on adventurers bringing treasure ("sequins") out from a dangerous wilderness; the idea that people write histories and popular non-fiction books about all the many adventurers infesting Beyond in the "Demon Princes"; or Interchange in The Killing Machine, which is predicated on kidnappings being so routine that the practice has developed formal institutions of arbitrage.

Vance's fiction, in other words, is adventurer-dense. Other adventurer-dense fictional universes which spring to mind are the Star Wars galaxy far, far away, Titan of the Fighting Fantasy books, and most D&D settings.

In adventurer-dense settings, you get an adventurer-friendly infrastructure developing. Institutions arise to facilitate what adventurers do, from your bustling inn brimming with hirelings and rumour, to your adventurer's guild, your market in ancient treasures and exotic weapons, your sages willing to shell out fortunes for rare collectibles, and so on. (Arguably, the true potential of adventurer-dense settings has never come close to being fully explored; would a system of adventurer insurance come into being? How about hireling labour exchanges? Or guilds for different adventurer types - woe betide a dungeoneer who is found to have been adventuring in a cave system or forest?)

For Tolkien, adventurers are rare. At any one time there appear to be roughly a dozen of them in the entire world, and they seem to be specifically chosen. They don't run into each other, and there is no adventuring infrastructure - Rivendell and Beorn are about it, at a stretch. His fiction is adventurer-sparse.

Gene Wolf tends to create adventurer-sparse settings, as do many of the more popular "big" fantasy authors, like Robert Jordan, David Eddings or Robin Hobb.

Is your world adventure-dense, or adventure-sparse, and what are the implications?

Vance's fiction, in other words, is adventurer-dense. Other adventurer-dense fictional universes which spring to mind are the Star Wars galaxy far, far away, Titan of the Fighting Fantasy books, and most D&D settings.

In adventurer-dense settings, you get an adventurer-friendly infrastructure developing. Institutions arise to facilitate what adventurers do, from your bustling inn brimming with hirelings and rumour, to your adventurer's guild, your market in ancient treasures and exotic weapons, your sages willing to shell out fortunes for rare collectibles, and so on. (Arguably, the true potential of adventurer-dense settings has never come close to being fully explored; would a system of adventurer insurance come into being? How about hireling labour exchanges? Or guilds for different adventurer types - woe betide a dungeoneer who is found to have been adventuring in a cave system or forest?)

For Tolkien, adventurers are rare. At any one time there appear to be roughly a dozen of them in the entire world, and they seem to be specifically chosen. They don't run into each other, and there is no adventuring infrastructure - Rivendell and Beorn are about it, at a stretch. His fiction is adventurer-sparse.

Gene Wolf tends to create adventurer-sparse settings, as do many of the more popular "big" fantasy authors, like Robert Jordan, David Eddings or Robin Hobb.

Is your world adventure-dense, or adventure-sparse, and what are the implications?

Wednesday, 13 May 2020

On the RPG Hobby's Structural Bias and Being D&D-Critical

Patrick Stuart, one of the players in my online Ryuutama campaign, put up this interesting post yesterday. In brief, Ryuutama is not really very good at producing the type of play that it presents itself as - a kind of Ghibli-meets-the-Oregon-Trail - and we've ended up really just doing old school D&D with a slightly different system.

Although I'm having fun running the campaign, this analysis is completely correct. What has happened so far has not really been very different to what would have happened if we were playing BECMI.

It's hard to know whether this is Ryuutama's fault or mine. I think partly it is down to weaknesses in the system, but also due to my own pre-existing biases; I didn't intend for the party to end up exploring a dungeon, but rolling on random tables led that way - and since I was the one who created the random tables, it's hard for me to lay the blame at anyone else's feet.

Nevertheless, all of this raises a set of more profound questions about the nature of 'feel' in RPGs. How do you successfully make a session or campaign have a certain atmosphere or mood, or emulate a particular genre or work of fiction?

My instinct is that there is what sociologists would probably call a 'structural bias' in the hobby, in that D&D has by far away the lion's share of the market and is the game through which most people first experience role playing. So regardless of its actual substantive qualities as a game, it dominates everybody's understanding of what an RPG is all about. All other things being equal, actual play leans towards being like D&D. There is a very faint inertia involved in anything that isn't dungeoneering.

The key phrase there, of course, is "all other things being equal". I don't mean for a second that it's impossible to play Pendragon or Call of Cthulhu or Traveller and not have it descend into dungeon exploration. That would be absurd. Clearly, there are other factors at work, including the substantive rules of whatever game is being played; the way they are presented; the art; the writing; the people involved in playing any given session of the game, and so on. Being "not D&D" is perfectly easily achievable when those factors align.

I increasingly, though, think the most important factor of all may be the people involved - their attitudes and what they want to achieve. Put another way, I am sure that if in my Ryuutama game we, the DM and players, had consistently encouraged each other to adopt a more Ghibli-like approach, we would have ended up with a more Ghibli-like campaign. We could, in short, have been more explicitly D&D-critical. When I was drawing up my random event tables, I could have reminded myself, "No, don't put anything remotely dungeonish in there - it wouldn't fit with the mood." I could have made the effort a tiny bit more strenuously to avoid leaning back on old crutches. A lot of 'feel', I mean, is really just down to effort and expectation.

One of the RPG campaign concepts I would dearly love to run would be an "in search of the Blue Wizards" game set in Middle Earth, with the PCs taking on the task of heading Eastwards, say from Rivendell, on a quest to find the two lost wizards and seek their aid in the war against Sauron. I have always been reticent to do so, because: a) it would involve a lot of work; b) it would be really hard not to have it end up as a railroad; but also, chiefly, c) I'm worried it would end up devolving into old school D&D. Maybe the problem here is just me - I don't trust myself to be sufficiently D&D-critical to make it work.

Although I'm having fun running the campaign, this analysis is completely correct. What has happened so far has not really been very different to what would have happened if we were playing BECMI.

It's hard to know whether this is Ryuutama's fault or mine. I think partly it is down to weaknesses in the system, but also due to my own pre-existing biases; I didn't intend for the party to end up exploring a dungeon, but rolling on random tables led that way - and since I was the one who created the random tables, it's hard for me to lay the blame at anyone else's feet.

Nevertheless, all of this raises a set of more profound questions about the nature of 'feel' in RPGs. How do you successfully make a session or campaign have a certain atmosphere or mood, or emulate a particular genre or work of fiction?

My instinct is that there is what sociologists would probably call a 'structural bias' in the hobby, in that D&D has by far away the lion's share of the market and is the game through which most people first experience role playing. So regardless of its actual substantive qualities as a game, it dominates everybody's understanding of what an RPG is all about. All other things being equal, actual play leans towards being like D&D. There is a very faint inertia involved in anything that isn't dungeoneering.

The key phrase there, of course, is "all other things being equal". I don't mean for a second that it's impossible to play Pendragon or Call of Cthulhu or Traveller and not have it descend into dungeon exploration. That would be absurd. Clearly, there are other factors at work, including the substantive rules of whatever game is being played; the way they are presented; the art; the writing; the people involved in playing any given session of the game, and so on. Being "not D&D" is perfectly easily achievable when those factors align.

I increasingly, though, think the most important factor of all may be the people involved - their attitudes and what they want to achieve. Put another way, I am sure that if in my Ryuutama game we, the DM and players, had consistently encouraged each other to adopt a more Ghibli-like approach, we would have ended up with a more Ghibli-like campaign. We could, in short, have been more explicitly D&D-critical. When I was drawing up my random event tables, I could have reminded myself, "No, don't put anything remotely dungeonish in there - it wouldn't fit with the mood." I could have made the effort a tiny bit more strenuously to avoid leaning back on old crutches. A lot of 'feel', I mean, is really just down to effort and expectation.

One of the RPG campaign concepts I would dearly love to run would be an "in search of the Blue Wizards" game set in Middle Earth, with the PCs taking on the task of heading Eastwards, say from Rivendell, on a quest to find the two lost wizards and seek their aid in the war against Sauron. I have always been reticent to do so, because: a) it would involve a lot of work; b) it would be really hard not to have it end up as a railroad; but also, chiefly, c) I'm worried it would end up devolving into old school D&D. Maybe the problem here is just me - I don't trust myself to be sufficiently D&D-critical to make it work.

Monday, 11 May 2020

"The World Cup of Duels" - Ryuutama AAR, Parts IV and V

[The recap for the last session can be found here. This is an omnibus edition for two sessions.]

The Characters

What Happened

The end of Part III saw our heroes underground on the shores of a vast and dark subterranean lake, with their buffoonish leader and champion Ogesana Fall unconscious and dying. They had vanquished a group of undead dwarfs and a water weird, but they had suffered heavily in the attempt. They retreated back to the Other Party's base camp to tend to Ogesana, regroup and lick their wounds.

The most immediate problem were rations. Put bluntly, the PCs had neglected to bring many of these at all, and had somewhat foolishly bartered the few they did have away in return for hallucinogenic mushrooms. The Other Party had some, but not enough for everybody to have something to eat for the three days it would take before Ogesana was fully conscious (let alone fully healed). So Kestrel spent the next two days fishing for blind cave fish in the underground lake, while Jojo tried his hand at getting some help from the goblin-ish things living close to the mouth of the caves, who had given their blessing to the PCs' expedition at the beginning of all of this. This returned a roasted giant cave cricket, enough to provide several days' worth of food for everybody, given in return for aforementioned hallucinogenic mushrooms (which the Great Shaman strongly desired) and out of affection for 'wise' Ogesana Fall, the human-man who had given such sage advice previously about the importance of water.

Days passed. Eventually Ogesana was nursed back to consciousness, and then restored with magical healing herbs. It was time, finally, to get back to exploring the lake.

Step one was to cross the water and investigate what was on the immediate far side, where there was apparently a cavern wall. There was much conversation about how to do this and whether it was wise to swim. Both Ogesana Fall and Sir Portos insisted on doing this. Eventually wiser heads prevailed when it was remembered that there were plenty of wooden doors higher up in the dungeon. These could be bound together to form a raft. Kyrie, a technician, was able to do this successfully, creating a raft that could bear three passengers.

There then followed a complicated argument. While the PCs and the Other Party were currently cooperating, their alliance only went so far. If only three people could traverse the lake at a time, and all of the passengers were from one party or the other, it could give that group an unfair advantage. In short, if there was any glory (or loot) to be had on the other side, they would get to it first. There was ostensibly an agreement in place about the disposal of any treasure after the expedition was over, but this would not of course apply to secret treasure. It was clear, then, that whichever three people went, there would have to be a mixture from both parties.

It was also clear that both Ogesana and Sir Portos would have to go, or neither. Their honour would not permit them to tolerate the other possibly getting the opportunity to be more courageous.

But unbeknownst to Ogesana, Jojo and Kestrel had been plotting to either kill or incapacitate Sir Portos for some time. This was not motivated by any particular animus (well, not entirely anyway) but because any and all treasure gained from the expedition - including the polliwoggle - would go to the winner of a duel to first blood between Ogesana and the Sir Portos once it was over. Since it was evident to everybody that Sir Portos would win such a contest easily, Jojo and Kestrel were naturally keen to find a way to avoid it ever taking place. Killing or injuring Sir Portos seemed the best way to do this. So they contrived that it should be they to go across on the raft, together with Kyrie from the Other Party.

On the way across, Kestrel and Jojo rather unsubtly probed Kyrie's loyalties to his master. It became obvious that Kyrie thought Sir Portos a ludicrous popinjay, but was bound by an oath, sworn to Sir Portos's family in perpetuity, because Kyrie's father had been saved from death by Sir Portos's. However, it was also established that there was nothing in the oath that would necessarily require Kyrie to intervene to prevent some plot being hatched by third parties against the knight.

Eventually the three of them arrived on the other side and found a small area of 'shore' with a man-made opening. They went into the opening and found a small chamber with a desiccated dwarf skeleton, still wearing armour, and carrying a ruby ring. On the far side was a staircase. Kestrel and Jojo knew that Ogesana would not be happy if any adventuring was done without him. But they were unwilling to both go back across the lake in the raft and leave Kyrie alone on the other side to explore. Eventually, through a complicated fox/chicken/grain arrangement, this was resolved and everybody was ferried to and fro until all were across the lake and gathered on the shore.

They crept up the stairs. At the top was a high, round chamber, with a podium or dias on top of which stood an 8 foot tall statue of a humanoid moray eel, like the statuette discovered earlier in the expedition, and the large shattered statue on the other side of the lake. It was carrying in one hand a sickle, with the other hand being empty but with space for something to be slotted inside. Its eyes were garnets.

Before anybody could do anything much, Kestrel took out the golden dagger handle which had been found near the shattered statue on the other side of the lake, and slotted it into this statue's hand. It instantly came alive and began bellowing and shrieking in a foul, alien tongue. Kestrel, because of the lingering after-effects of his mushroom trip, was able to understand the statue as demanding to know there whereabouts of 'the Twin'. It then marched off its podium and headed for the doorway, cutting down Kyrie with its sickle.

A general melee developed. Sir Portos dealt the statue several lusty blows with his guisarme, but the blade could not damage it. The PCs attempted various distractions, including snatching up a broken chest from somewhere in a corner and trying to use it to cover the statue's head, thus blinding it. Eventually it became clear, though, that the thing was not trying to kill anybody, in particular but was simply heading for the staircase and attacking anything in its way. They decided to let it go, and follow behind - although Sir Portos had to be persuaded by Ogesana not to continue the fight.

Ogesana and Maria remained to make romantic declarations to each other and tend Kyrie. Jojo, Kestrel and Sir Portos chased the statue downstairs and found it marching to the other side of the lake, apparently intending to march on the bottom of the lake and eventually submerge itself and come out on the opposite shore. They followed it in the raft and watched it approach the shattered statue. It was by now clear what it meant by 'the Twin'. They fanned out behind it and watched, fully prepared to do battle. Having stabilised Kyrie, Ogesana left him in Maria's care and charged down to join the others, using the aforementioned chest as a makeshift boat. A furious fight developed as the statue came after them, apparently in the belief they had something to do with the Twin's destruction. Kestrel was severely wounded. But eventually, through Ogesana's ingenuity - hiding behind the statue's legs while Sir Portos poked at it with his guisarme so that eventually it toppled over and was half-smashed by its own weight - they were victorious and managed to disarm the statue.

They decided that, rather than kill it, they would attempt to communicate with it. This they did with pictograms scratched in the sand with a sword, and gesture, aided by Kestrel's ability to understand what the statue said (although he lacked the ability to speak in return). They learned that somebody must have snatched the dagger from the statue's hand long ago and used it to destroy 'the Twin'; they surmised this was Cuthbert, the author of the account written on slate they had discovered in a chamber closer to the surface of the caves. They also learned that Cuthbert's dwarves had all gone mad and drowned themselves in the lake, apparently through worship of the moray god. Finally, they discovered that the underground lake stretched far off into infinity, eventually merging with the endless ocean which was the source of all water in the universe, and that one must not stray too far into it, because eventually one would find oneself borne away on currents that would take one away into that never-ending vastness.

The task was clear. Find and recover the tadpole, but do not get swept into the infinite plane of water.

But the raft only had space for three. Who would go, and who would stay? Clearly Ogesana and Sir Portos would insist. For some time, it seriously seemed as though a system of duels would have to be fought to decide who else would do it - a knock-out 'world cup' affair. Eventually this seemed to have been abandoned - although no final decision was reached.

*

And that was the end of the fifth session. I really enjoyed both this session and the previous one - lots of dastardly plotting took place, as well as some good creative thinking. The conversation with the statue was also full of funny misunderstandings and complications which I can't do justice in a blog post. But I realised at the end of it that I had abandoned Ryuutama's combat system for the most part and was really running it rather like D&D. The system itself is a plan that hasn't quite sustained contact with the enemy.

The Characters

- Jojotekina Gyoza ("Jojo"), a technical-type minstrel armed with a flute

- Kestrel, an attack-type hunter who bears a mysterious scroll that he believes he must deliver to somebody, whose identity he does not know

- Ogesana Fall, a magic-type noble, and his trusty but ignoble donkey, Bartholemew

- Virid, the GMPC (Ryuutama has these, but they don't do too much and don't really appear initially), a mysterious green-bearded old man

- Sir Portos of Underhill, Maria the Hedgewitch and Kyrie the Nondescript Henchman, three NPC adventurers, referred to collectively as "the Other Party"

What Happened

The end of Part III saw our heroes underground on the shores of a vast and dark subterranean lake, with their buffoonish leader and champion Ogesana Fall unconscious and dying. They had vanquished a group of undead dwarfs and a water weird, but they had suffered heavily in the attempt. They retreated back to the Other Party's base camp to tend to Ogesana, regroup and lick their wounds.

The most immediate problem were rations. Put bluntly, the PCs had neglected to bring many of these at all, and had somewhat foolishly bartered the few they did have away in return for hallucinogenic mushrooms. The Other Party had some, but not enough for everybody to have something to eat for the three days it would take before Ogesana was fully conscious (let alone fully healed). So Kestrel spent the next two days fishing for blind cave fish in the underground lake, while Jojo tried his hand at getting some help from the goblin-ish things living close to the mouth of the caves, who had given their blessing to the PCs' expedition at the beginning of all of this. This returned a roasted giant cave cricket, enough to provide several days' worth of food for everybody, given in return for aforementioned hallucinogenic mushrooms (which the Great Shaman strongly desired) and out of affection for 'wise' Ogesana Fall, the human-man who had given such sage advice previously about the importance of water.

Days passed. Eventually Ogesana was nursed back to consciousness, and then restored with magical healing herbs. It was time, finally, to get back to exploring the lake.

Step one was to cross the water and investigate what was on the immediate far side, where there was apparently a cavern wall. There was much conversation about how to do this and whether it was wise to swim. Both Ogesana Fall and Sir Portos insisted on doing this. Eventually wiser heads prevailed when it was remembered that there were plenty of wooden doors higher up in the dungeon. These could be bound together to form a raft. Kyrie, a technician, was able to do this successfully, creating a raft that could bear three passengers.

There then followed a complicated argument. While the PCs and the Other Party were currently cooperating, their alliance only went so far. If only three people could traverse the lake at a time, and all of the passengers were from one party or the other, it could give that group an unfair advantage. In short, if there was any glory (or loot) to be had on the other side, they would get to it first. There was ostensibly an agreement in place about the disposal of any treasure after the expedition was over, but this would not of course apply to secret treasure. It was clear, then, that whichever three people went, there would have to be a mixture from both parties.

It was also clear that both Ogesana and Sir Portos would have to go, or neither. Their honour would not permit them to tolerate the other possibly getting the opportunity to be more courageous.

But unbeknownst to Ogesana, Jojo and Kestrel had been plotting to either kill or incapacitate Sir Portos for some time. This was not motivated by any particular animus (well, not entirely anyway) but because any and all treasure gained from the expedition - including the polliwoggle - would go to the winner of a duel to first blood between Ogesana and the Sir Portos once it was over. Since it was evident to everybody that Sir Portos would win such a contest easily, Jojo and Kestrel were naturally keen to find a way to avoid it ever taking place. Killing or injuring Sir Portos seemed the best way to do this. So they contrived that it should be they to go across on the raft, together with Kyrie from the Other Party.

On the way across, Kestrel and Jojo rather unsubtly probed Kyrie's loyalties to his master. It became obvious that Kyrie thought Sir Portos a ludicrous popinjay, but was bound by an oath, sworn to Sir Portos's family in perpetuity, because Kyrie's father had been saved from death by Sir Portos's. However, it was also established that there was nothing in the oath that would necessarily require Kyrie to intervene to prevent some plot being hatched by third parties against the knight.

Eventually the three of them arrived on the other side and found a small area of 'shore' with a man-made opening. They went into the opening and found a small chamber with a desiccated dwarf skeleton, still wearing armour, and carrying a ruby ring. On the far side was a staircase. Kestrel and Jojo knew that Ogesana would not be happy if any adventuring was done without him. But they were unwilling to both go back across the lake in the raft and leave Kyrie alone on the other side to explore. Eventually, through a complicated fox/chicken/grain arrangement, this was resolved and everybody was ferried to and fro until all were across the lake and gathered on the shore.

They crept up the stairs. At the top was a high, round chamber, with a podium or dias on top of which stood an 8 foot tall statue of a humanoid moray eel, like the statuette discovered earlier in the expedition, and the large shattered statue on the other side of the lake. It was carrying in one hand a sickle, with the other hand being empty but with space for something to be slotted inside. Its eyes were garnets.

Before anybody could do anything much, Kestrel took out the golden dagger handle which had been found near the shattered statue on the other side of the lake, and slotted it into this statue's hand. It instantly came alive and began bellowing and shrieking in a foul, alien tongue. Kestrel, because of the lingering after-effects of his mushroom trip, was able to understand the statue as demanding to know there whereabouts of 'the Twin'. It then marched off its podium and headed for the doorway, cutting down Kyrie with its sickle.

A general melee developed. Sir Portos dealt the statue several lusty blows with his guisarme, but the blade could not damage it. The PCs attempted various distractions, including snatching up a broken chest from somewhere in a corner and trying to use it to cover the statue's head, thus blinding it. Eventually it became clear, though, that the thing was not trying to kill anybody, in particular but was simply heading for the staircase and attacking anything in its way. They decided to let it go, and follow behind - although Sir Portos had to be persuaded by Ogesana not to continue the fight.

Ogesana and Maria remained to make romantic declarations to each other and tend Kyrie. Jojo, Kestrel and Sir Portos chased the statue downstairs and found it marching to the other side of the lake, apparently intending to march on the bottom of the lake and eventually submerge itself and come out on the opposite shore. They followed it in the raft and watched it approach the shattered statue. It was by now clear what it meant by 'the Twin'. They fanned out behind it and watched, fully prepared to do battle. Having stabilised Kyrie, Ogesana left him in Maria's care and charged down to join the others, using the aforementioned chest as a makeshift boat. A furious fight developed as the statue came after them, apparently in the belief they had something to do with the Twin's destruction. Kestrel was severely wounded. But eventually, through Ogesana's ingenuity - hiding behind the statue's legs while Sir Portos poked at it with his guisarme so that eventually it toppled over and was half-smashed by its own weight - they were victorious and managed to disarm the statue.

They decided that, rather than kill it, they would attempt to communicate with it. This they did with pictograms scratched in the sand with a sword, and gesture, aided by Kestrel's ability to understand what the statue said (although he lacked the ability to speak in return). They learned that somebody must have snatched the dagger from the statue's hand long ago and used it to destroy 'the Twin'; they surmised this was Cuthbert, the author of the account written on slate they had discovered in a chamber closer to the surface of the caves. They also learned that Cuthbert's dwarves had all gone mad and drowned themselves in the lake, apparently through worship of the moray god. Finally, they discovered that the underground lake stretched far off into infinity, eventually merging with the endless ocean which was the source of all water in the universe, and that one must not stray too far into it, because eventually one would find oneself borne away on currents that would take one away into that never-ending vastness.

The task was clear. Find and recover the tadpole, but do not get swept into the infinite plane of water.

But the raft only had space for three. Who would go, and who would stay? Clearly Ogesana and Sir Portos would insist. For some time, it seriously seemed as though a system of duels would have to be fought to decide who else would do it - a knock-out 'world cup' affair. Eventually this seemed to have been abandoned - although no final decision was reached.

*

And that was the end of the fifth session. I really enjoyed both this session and the previous one - lots of dastardly plotting took place, as well as some good creative thinking. The conversation with the statue was also full of funny misunderstandings and complications which I can't do justice in a blog post. But I realised at the end of it that I had abandoned Ryuutama's combat system for the most part and was really running it rather like D&D. The system itself is a plan that hasn't quite sustained contact with the enemy.

Friday, 8 May 2020

The Sweet Spot

I have been continuing the Ryuutama campaign and will post some 'omnibus' AP reports on the blog shortly. But running these sessions have got me thinking about the timing of sessions.

I'd be interested to hear people's thoughts on the ideal time length of an RPG session. The immediate reaction people tend to have, and which I myself would once have had, with these things is to just go, 'How long is a piece of string?' But now I'm not so sure. Because of my own time constraints, the session I've been running tend to be about 90 minutes long, and almost invariably that feels - to me at least - like we are just hitting our stride.

This is in some respects good, because there is almost nothing in life to which the motto, 'Always leave them wanting more' is not applicable and solid advice. But 90 minutes I think errs too far on the wrong side of that principle - it isn't quite satisfying enough. What I think it indicates is that 90 minutes would be a good point to have a break, before another 90 minute second half, as it were.

An additional argument for this is that I have come to believe, for pseudoscientific reasons, that 90 minutes is a kind of sweet spot for human beings in general - a natural breaking point in the attention cycle, something to do with the ways our brain activity fluctuates throughout the day and night. Most people have sleep cycles of around 90 minutes, for instance, and it may be why feature films are about that long. Teaching classes at university has also taught me that an hour is usually too short, but two hours are too long - 90 minutes has a way of working out at being 'just right'. This would suggest to me that 90 minutes has a natural rhythmic feel to it at a phenomenological level, but also that 3 hours with a short break in the middle may be the perfect amount of gaming, since 90 minutes isn't quite enough to really make major progress.

I'd be interested to hear people's thoughts on the ideal time length of an RPG session. The immediate reaction people tend to have, and which I myself would once have had, with these things is to just go, 'How long is a piece of string?' But now I'm not so sure. Because of my own time constraints, the session I've been running tend to be about 90 minutes long, and almost invariably that feels - to me at least - like we are just hitting our stride.

This is in some respects good, because there is almost nothing in life to which the motto, 'Always leave them wanting more' is not applicable and solid advice. But 90 minutes I think errs too far on the wrong side of that principle - it isn't quite satisfying enough. What I think it indicates is that 90 minutes would be a good point to have a break, before another 90 minute second half, as it were.

An additional argument for this is that I have come to believe, for pseudoscientific reasons, that 90 minutes is a kind of sweet spot for human beings in general - a natural breaking point in the attention cycle, something to do with the ways our brain activity fluctuates throughout the day and night. Most people have sleep cycles of around 90 minutes, for instance, and it may be why feature films are about that long. Teaching classes at university has also taught me that an hour is usually too short, but two hours are too long - 90 minutes has a way of working out at being 'just right'. This would suggest to me that 90 minutes has a natural rhythmic feel to it at a phenomenological level, but also that 3 hours with a short break in the middle may be the perfect amount of gaming, since 90 minutes isn't quite enough to really make major progress.

Tuesday, 5 May 2020

Dungeoneering as Tactical Combat

When I have a spare moment, I have been enjoying watching this guy's actual plays of the old game, Terror from the Deep.

It got me wondering whether anybody had experimented with running D&D as a kind of tactical wargame, meaning in other words a one-on-one campaign between a DM and a single player controlling an entire party of PCs exploring dungeons and hexmaps and so on.

I often have players create two PCs in a D&D campaign, so that there are 'spares' on hand when PCs (inevitably) die. But I have never gone beyond that. It strikes me that it might be fun.

It got me wondering whether anybody had experimented with running D&D as a kind of tactical wargame, meaning in other words a one-on-one campaign between a DM and a single player controlling an entire party of PCs exploring dungeons and hexmaps and so on.

I often have players create two PCs in a D&D campaign, so that there are 'spares' on hand when PCs (inevitably) die. But I have never gone beyond that. It strikes me that it might be fun.

Monday, 4 May 2020

Killers' Path

Imperial rule in the north found it expedient to deploy assassins to help achieve its ends. These were trained almost from birth, and divided into groups by specialism - strangling, poisoning, stabbing, and so on. What begins in utility ends in ritual: over the centuries these groups evolved into formal religious cults, devoted not only to the Emperor but also to murder itself as a holy act, and believing purposeless killing to be the ultimate celebration of the triumph of the uncaring cosmos over man’s petty goals and desires. Their religiosity enabled them to survive whatever precipitated the collapse of the Empire, and thereafter they roamed the region where the Dark River meets the Great North Road, further refining their arts and the application of them, and preying at random on the populace.

It took the Lady to unify them and to found what became the town of Killers’ Path. Nobody knows to which cult she belonged, and it has become important subsequently for her origins to remain mysterious; but what is known is that she was a prominent, skilled assassin, well-versed in her technique and devoted like no other to the cause of empty and premature death. Yet she herself became the target of rivals, and was murdered by them - only to come back from the dead a month later with a revolutionary message. This was that it is possible to cheat the cosmos and defeat death through will alone, and in doing so to return fully alive rather than in the empty parody of life that is undeath. She brought the different cults together with this tale of hope, and created with them a settlement which grew gradually into a burgh.

Killers’ Path is now, at a superficial glance, an ordinary market town, filled with ordinary freemen and their families and servants. But the cults remain. By no means every freeman of the town is a member, but a significant proportion are, and they play out a half-secret ‘Game’ alongside the comings and goings of mainstream society - one in which ritualised murder is permitted and encouraged. The rules of the Game are straightforward. At the beginning of a Round, one member from each cult is selected at random to be the ‘Hare’ - that is, the target for assassination - for another cult, again chosen at random. Over the course of the Round, usually lasting a year and a day, the cults each attempt to kill their respective Hares however they see fit, the only other rule being that they must kill no other citizen of the town, including members of other cults.

This is an exercise in brinksmanship. The later the assassination takes place in the Round, the better; the last cult to kill its Hare is the winner. But failure to kill the Hare at all by the last day of the Round means shameful defeat. The aim of each cult, then, is to kill its Hare as late as it can bear the risk of leaving it. This means that for most of the time the cults are simply plotting and scheming; it is only in the weeks leading up to the end of a given Round that the ‘action’ truly takes place. Naturally enough, however, each cult also spends most of each Round plotting to protect its Hare from assassination so as to frustrate whatever cult is targeting it this time. The result is that, each Round, all of the cults are engaged in a complicated dance of espionage and counter-espionage as they plot their final attacks and attempt to uncover - and hinder - each others’ schemes. All of this takes place under the noses of the inhabitants of the town, of course, who feign ignorance even as they await patiently the ‘sport’ to begin when the Round draws to its conclusion.

The Lady still rules Killers’ Path, though she is rarely seen. When she is, she appears as she has for as long as the living can remember - half way between middle-aged and old, handsome and cold, supremely calm, her jet black hair touched here and there with grey. She has no apparent servants, nor entourage, and lives alone in a tower in the centre of a small courtyard hidden behind some townhouses off a quiet street. Yet almost all obey her without question. She is as close as one can come to being a living God, and the members of the cults naturally take her word as law, her commands as instructions. This is reinforced by what is common knowledge in Killers’ Path: any who go against a decree from the Lady or act against her interests do not remain alive in the town for long.

It took the Lady to unify them and to found what became the town of Killers’ Path. Nobody knows to which cult she belonged, and it has become important subsequently for her origins to remain mysterious; but what is known is that she was a prominent, skilled assassin, well-versed in her technique and devoted like no other to the cause of empty and premature death. Yet she herself became the target of rivals, and was murdered by them - only to come back from the dead a month later with a revolutionary message. This was that it is possible to cheat the cosmos and defeat death through will alone, and in doing so to return fully alive rather than in the empty parody of life that is undeath. She brought the different cults together with this tale of hope, and created with them a settlement which grew gradually into a burgh.

Killers’ Path is now, at a superficial glance, an ordinary market town, filled with ordinary freemen and their families and servants. But the cults remain. By no means every freeman of the town is a member, but a significant proportion are, and they play out a half-secret ‘Game’ alongside the comings and goings of mainstream society - one in which ritualised murder is permitted and encouraged. The rules of the Game are straightforward. At the beginning of a Round, one member from each cult is selected at random to be the ‘Hare’ - that is, the target for assassination - for another cult, again chosen at random. Over the course of the Round, usually lasting a year and a day, the cults each attempt to kill their respective Hares however they see fit, the only other rule being that they must kill no other citizen of the town, including members of other cults.

This is an exercise in brinksmanship. The later the assassination takes place in the Round, the better; the last cult to kill its Hare is the winner. But failure to kill the Hare at all by the last day of the Round means shameful defeat. The aim of each cult, then, is to kill its Hare as late as it can bear the risk of leaving it. This means that for most of the time the cults are simply plotting and scheming; it is only in the weeks leading up to the end of a given Round that the ‘action’ truly takes place. Naturally enough, however, each cult also spends most of each Round plotting to protect its Hare from assassination so as to frustrate whatever cult is targeting it this time. The result is that, each Round, all of the cults are engaged in a complicated dance of espionage and counter-espionage as they plot their final attacks and attempt to uncover - and hinder - each others’ schemes. All of this takes place under the noses of the inhabitants of the town, of course, who feign ignorance even as they await patiently the ‘sport’ to begin when the Round draws to its conclusion.

The Lady still rules Killers’ Path, though she is rarely seen. When she is, she appears as she has for as long as the living can remember - half way between middle-aged and old, handsome and cold, supremely calm, her jet black hair touched here and there with grey. She has no apparent servants, nor entourage, and lives alone in a tower in the centre of a small courtyard hidden behind some townhouses off a quiet street. Yet almost all obey her without question. She is as close as one can come to being a living God, and the members of the cults naturally take her word as law, her commands as instructions. This is reinforced by what is common knowledge in Killers’ Path: any who go against a decree from the Lady or act against her interests do not remain alive in the town for long.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)