Creator of Yoon-Suin and other materials. Propounding my half-baked ideas on role playing games. Jotting down and elaborating on ideas for campaigns, missions and adventures. Talking about general industry-related matters. Putting a new twist on gaming.

Monday, 30 December 2024

2024 in Review

Monday, 23 December 2024

The Fiction Becomes the System for Advancement; Or, Something Needs to be Heavy

In the comments on a recent entry, the subject of rules-lite games and level advancement came up. It has always been my position that problems with rules-lite games arise when they become so rules-lite that they lack sufficient 'crunch' to be used in for a long-term, open-ended campaign. A long-term campaign needs advancement to give impetus to proceedings, and this is harder to achieve in direct proportion to how ephemeral the rules feel. The good thing about advancement in D&D, for instance, is that by going up in levels new possibilities are opened by virtue of the fact that the system incorporates many options and add-ons - there are new spells to learn, new magic items to find, new abilities to develop (depending on one's edition of choice). This is harder to achieve with a rules-lite system where all one really gets to do is fiddle around with a very limited number of stats or abilities.

However, I am persuaded, as commenter diessa puts it in the post in question, there is a case to be made that one can - if only one is of a mind to - run a rules-lite campaign in which 'the fiction becomes the system for advancement'. The idea here is that the PCs have goals that are intrinsic to the 'fiction' itself rather than extrinsic ones to do with improving stats, hit points or whatever - solving murders, say, or social advancement, or earning lots of money, or realising some project or objective. And here it wouldn't matter that the rules are 'lite', so to speak, because they would only exist in order to provide a basic framework in which 'the fiction' can evolve.

I can buy this to a certain extent, but I think it misses something important, which is that in order to get to a point at which 'the fiction becomes the system for advancement', there still needs to be part of the campaign that is heavy in the sense of requiring lots of careful thought and probably a great deal of procedural moving parts (but which might be hidden from the players themselves). For instance, I can easily imagine a long-running campaign with a rules-lite system being successful if it chiefly involved investigation - a crime procedural, for instance, or an Unknown Armies or Call of Cthulhu-style paranormal mystery. But I can't really imagine either of those things working without the DM having to invest a lot of time in figuring out ways to systematise the distribution of clues, connections between NPCs, random events, flowcharts dictating what happens if the PCs do X and then Z rather than Y, and so on and so forth; there will still have to be weight, in this sense, but placed behind the scenes rather than being foregrounded in the player-facing rules.

Similarly, I can imagine a long-running campaign with a rules-lite system working if the PCs were, let's say, merchants or traders or businessmen or whatever. But, again, I can't really imagine it working without considerable weight being placed within the commercial or financial aspects of the game - without, say, a way of figuring out what is profitable, in what context, and where.

In short, the argument that I think I am making is that in order for a long-running, open-ended campaign to be a success there is a requirement, even in the context of the rules as such being 'lite', for there to be an aspect of play which is heavy. There has to be something that has sufficient heft to bear the load of sufficient interest and intrigue in order to keep the campaign above water. I am not convinced that it is possible to sustain long-term gaming with mere 'fictional advancement' alone.

Thursday, 19 December 2024

My Shoe is Safe

Yesterday's quiz was a toughie. In it, to recap, commenters were encouraged to guess at what the following pieces of art, generated by Substack's own AI image generator, represented. Here, to begin with, are the answers:

1. Minotaur

2. Troll

3. Orc

Tuesday, 17 December 2024

Satan Illustrated My Bestiary

I have spilt rather a lot of ink dealing with the subject of AI art. (Rather too much perhaps - see previous posts here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

Today I spent an idle moment nibbling at the forbidden fruit by typing some famous monster names into Substack's particular AI image generator. This was based on the theory that if you want to make some pictures of monsters, Satan is probably the ideal artist.

I had originally planned to write an extensive post on this subject, but rapidly discovered a fun way to run a quiz instead. So here goes. Below, I will post a series of numbered pictures as illustrated by Satan. Your job, in the comments, is to guess what they represent. Some are easy! Some are hard! Give it a go. The winner receives unending adulation and glory. The losers - level drain and half hp. Answers to be revealed on Friday.

First, though, I must share with you the great hilarity that ensued when I typed in the words 'Keir Starmer':

I don't know who that man is, but I can tell you that Kier Starmer very much wishes he looked like him. Who the hell is the guy lurking next to him, though?

Anyway, I digress. Here are the monsters. To repeat, put your guesses for each in the comments.

1.

2.

3.

Friday, 13 December 2024

What I Would Do If I Owned D&D

Since in my previous post I raised the question, it is only fair that I deliver my own thoughts on the important matter of what I would do if I owned D&D.

I find myself genuinely split. On the one hand, I think D&D occupies an important role as a sort of universal language, and that its middle-of-the-roadness and basic banality, as a Tolkienesque fantasy RPG denuded of all the things that made Tolkien interesting and worthwhile, is in its own way useful. There is a reason why McDonald's, M&S, Next, Disney princesses, Bond films, etc., exist - it is to provide an easy solution to the question of 'What shall we eat/wear/watch tonight?' The more eccentric and distinctive something is, the harder it will be to get buy-in from those who do not share the eccentricity in question.

Hence, 'blandified, bowdlerized Tolkien with some bits and pieces stolen from pulp fantasy' is much more likely to appeal to a group of five random gamers who want to put a campaign together than is 'Egyptian/meosamerican style megadungeon inside a crocodile's brain' - while one or even two of the group will love the latter idea, the rest will be put off by it, whereas there is a good chance that all five will at least tolerate the former.

There is therefore a space for doing blandified, bowdlerized Tolkien well, and in this respect I suppose it's actually quite difficult to improve on what WotC are already doing. They serve up RPG Big Macs and they do it in such a way as to satisfy the widest range of potential gamers they possibly can. It is not to my taste, but even I eat Big Macs sometimes when it's the easiest and most readily available thing on offer. So the very shot answer to what I would do if I owned D&D could be very straightforward: do what WotC currently do but a bit better. (Chiefly, I would change the art direction so as to be much more John Howe-style understated grandeur, and much less modern-video-game-illustration blandness.)

That's a boring answer, though, and also doesn't really reflect the basic setup of the thought experiment, which is that I am supposed to be imaginging myself as possessing vast wealth and not particularly having any interest in turning a profit. Once you put things that way, all the bets are off and you can start entirely from scratch.

So I am strongly tempted, then, to say that if I owned D&D I would go in the opposite direction - I would be a fantasy maximalist. I would have a set of relatively simple core mechanics and I would commission a range of writers and artists to produce a properly compelling mixture of genuinely novel and fresh settings, and I would foreground procedural generation through random tables throughout. I would put the emphasis entirely on dungeoneering and sandbox exploration, and would eschew 'character' as a central element of play. And while I would not by any means cut down on things like bestiaries and spell lists, I would emphasise the toolkit element of the rules - I would make it very plain that the rules are there to facilitate DMs doing their own imaginative things (inventing monsters, spells, etc.) easily and quickly.

But now that I re-read that paragraph I increasingly wonder whether I am not simply saying in the end that I would cannibalise existing D&D with an OSR mentality (since the OSR basically did all of the things I suggest) and, indeed, perhaps just in the end institutionalise and mainstream what the OSR was all about. This might not be as popular as D&D is now, but it would I think be better, and that's what counts.

Monday, 9 December 2024

What Would You Do If You Owned D&D?

What would you do if you owned D&D?

I ask because the question has taken on a very small amount of pertinence in the last couple of weeks, in the aftermath of Elon Musk's having expressed his views about the game. I don't wish to get into the ins and outs of those views here and I would like to leave politics entirely to one side. I would just like to raise for observation the interesting point that we now live in an age in which there are lots of very nerdy people who also have veritable bag of holding of billions of dollars in cash - and, that since nerds are much more likely to play D&D than the average person, this makes the purchase of D&D by an eccentric billionaire are not-entirely unthinkable proposition.

Reel off the list: Elon Musk. Bill Gates. Mark Zuckerberg. Peter Thiel. Sundar Pichai. Sam Altman. And so on and so on; the question that is most appropriate to ask is not 'How many of these people have played D&D?' but 'How many of them haven't?' And who is to write off the possibility that one of these people may some day decide that they would actually quite like to be the one who gets to make his favourite role playing game his plaything? The thing about eccentric billionaires is that they do eccentric things with their money. Could we see emerging a future in which D&D, in the manner of a down-at-heel sport club bought by Hollywood Stars, becomes a trophy of of the super-rich?

Elon Musk himself was openly musing in the aftermath of the recent farrago (one assumes jokingly, though possibly not) about buying Hasbro, whose market capitalisation is 'only' about $9 billion. What would you do vis-a-vis D&D if you had just bought Hasbro for $9 billion? Or, for that matter, if you had just prized the D&D IP from Wizards of the Coast, presumably for rather less than $9 billion, and made it your own?

To keep this organised and manageable, I recommend limiting yourself to decisions across up to three axes.

1 - What would you do with respect to the rules?

2 - What changes would you make to the default setting?

3 - What settings would you commission? Bear in mind you are an eccentric multi-billionaire. Probably any book or film franchise is achievable. Which would you pick?

Tuesday, 3 December 2024

Twelve Module Ideas

Apropos of nothing, here are 12 ideas for modules with one-sentence descriptors. If you like this post, write your own variant.

1. The Tophet of the Giants. A cemetery of tombs for the sacrificed children of an ancient race of giants.

2. The Golem Foundry. A huge underground complex where metal is melted and cast for the creation of different types (copper, iron, gold, etc.) of golem; each step in the process takes place in a different network of chambers, performed by a different type of servitor.

3. The Roc's Nest. A gargantuan bundle of tree trunks and boulders moulded together by a titanic bird; within are giant fleas, ticks and other parasites; insects of any and all different kinds; scavengers and raiders living off leftovers; and the occasional treasure dropped by a victim before being devoured.

4. The Palace of Death. A place where the nobility of a long-lost civilisation would go to be euthanised in various inventive, beautiful, spectacular and horrifying ways; their ghosts haunt the labyrinthine corridors.

5. The Lost World. A tepui on top of which is a remnant of an ancient civilisation or race of monsters.

6. The Leviathans' Graveyard. A remote shore where gargantuan whales go to die; their huge corpses litter the coast, providing shelter to may different inhabitants.

7. The Old Forest. A copse of trees which, when entered, is of vastly greater size than it first appears.

8. The Floating Mass. A huge natural raft of vegetation which has arrive on a coastline, bringing with it strange beings from a distant land.

9. The Temple that Fell Down the Mountain. A high mountaintop temple, long inaccessible to ordinary mortals, has fallen in a landslide, its ancient treasures scattered across the mountainside.

10. The City Descended. A famous floating sky-city has made a hitherto-unprecedented 'landing' due to some emergency or overriding imperative; something has happened to the inhabitants.

11. The Oubliette Unlocked. A great subterranean prison into which an ancient race flung their outcasts and exiles, now rediscovered by miners and accidentally opened.

12. The City of the Mist. A city, long ago cursed to remain permanently shrouded in fog, has had its curse miraculously lifted after centuries - to reveal a place very different to what what was there before.

Friday, 29 November 2024

Bridging the Representative Diversity Divide

You may have heard that there has been something of a kerfuffle lately, concerning attacks made by various of Wizards of the Coast's stable of designers and hangers-on against the older editions of D&D and their various insensitivities about language, lack of representation of non-white people, casual depictions of slavery, and so on and so forth. This is, apparently, happening in tandem with a gradual 'wokeification', if I can use that term, of the game in its most recent iterations, opinions about which - naturally enough nowadays - tend to cleave along culture war lines.

This highlights the extent to which people in the culture war on both sides generally tend to interpret each other's conduct in the least charitable way possible, and thereby convince themselves that people with opposing views are evil and malevolent rather than just adopting a different perspective.

I thought therefore it might be useful to give the most charitable interpretations I can think of to the two sides in the 'representativeness' debate in order to see if there can be an armistice of some kind. Because I think in particular people who are in favour of what I will call representative diversity tend to interpret the kneejerk reaction against 'wokeness' as being evidence of barely concealed or inchoate racism, when actually it's best to descibe it as a pretty understandable feeling of being unfairly demonised.

Let's start, then, by putting the case for representative diversity at its strongest: for years and years it was mostly straight white men (or, let's face it, straight white adolescent boys) who played D&D, and they tended rather unthinkingly and generally unconsciously to behave in ways that were insensitive or exclusionary. A great example of this, not from D&D, actually comes from Palladium Fantasy, in which homosexuality appears in a list of variants of insanity (in my memory - I don't have the book in front of me - this is fairly early on in the text itself). Other more visually obvious examples would be the tendency to only ever depict women as looking either like supermodels or else witches or hags, or to only ever depict black or brown people in the context of being 'savages'. All of this was entirely understandable in historical terms simply because it is an ineluctable feature of the human experience that people tend to stereotype or typecast other people who don't physically resemble them. But it put off people who didn't fit into a particular paradigm and, hey, why put people off? Why not make the game more 'inclusive'?

What, then, could be the reason for the counter-reaction? Let's again put the case at its strongest and with its most charitable interepretation. It has I think three distinct limbs, though these interrelate for reasons which will be obvious.

The first is that people can smell a rat with respect to the way in which companies like Wizards of the Coast operate. There is absolutely nothing genuine or principled about the way representative diversity is put into effect at the commercial level - it is happening simply because D&D for a long time had a core market of nerdy straight white adolescent boys and that market is in relative terms getting smaller and smaller. The diversity is there because of entirely cynical reasons - it isn't because Wizards of the Coast are a charitable foundation trying to improve race relations across the Western world, or making their own game more inclusive because they're just such nice guys. Fake sincerity is grating to everyone, and some people (I include myself in this) have a fine-tuned sensitivity against it.

The second is that nerds are nerds, and some nerds care about things 'making sense' in particular ways. Until very recently in human history most societies simply were not racially diverse in anything like the way they are now. And so something feels 'off' about presenting fantasy medieval societies as looking, in racial terms, like a cosmopolitan modern city. Similarly, there have never been human societies in which men and women's roles have been exactly the same and not in any way, to use modern parlance, 'gendered'. Here, the opposition mainly comes from a position of a desire for verissimilitude. The standard response to this - 'This is a game with magic and dragons in, so why do you care about realism?' - is well-known, but slightly unfair; when it comes to fantasy settings, tastes for the level of realism that different people prefer simply vary.

The third is that the trouble with trying to increase representative diversity is that it is difficult to do it in such a way as to not appear to be acting sanctimoniously and/or snidely. Too often it comes alongside a (consciously or unconsciously) mean-spirited insinuation: 'You have a problem with this, do you? It's because you're a racist. You are, aren't you?' For people who are perfectly well aware that they have no racist bones in their own bodies, and who have just been innocently enjoying pretending to be an elf for years and have never 'excluded' anybody from anything, there is something galling about being implicitly cast as a villain in this way. And in this regard it bears emphasising that respresentative diversity is very frequently, indeed all too frequently, framed by an assertion that the hobby would just be 'better' in some sense if it was less 'pale, male and stale'. There are only so many occasions on which a person can accept being told that their very presence - or the presence of their type of person - is undesirable before they start to simply get pissed off. And the anger is justified; if everybody is entitled to equal concern and respect, then that means everybody is.

Both sides in the representative diversity debate, such as it is, therefore have good faith arguments. And when two people are approaching a disagreement from a position of good faith, what tends to happen - if they don't listen to each other properly - is that they start to convince themselves that because their own position is good, the disagreement can only have arisen becaues the other side is bad. They begin to forget that it is possible for people to disagree for good reason. And this makes the disagreement more intractable, because the participants grow more convinced that compromise is undesirable (since compromise with somebody who is definitionally bad can only ever be an unjustified concession). This is, obviously, to be regretted, because it transforms such disagreements into winner-takes-all conflicts when the truth is that the stakes are probably considerably lower than either side realises. A more sensible public discourse is available - in every respect.

Wednesday, 20 November 2024

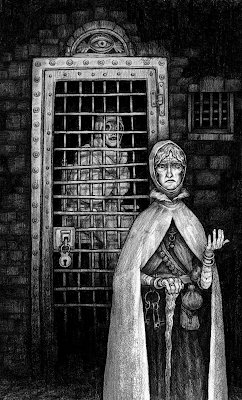

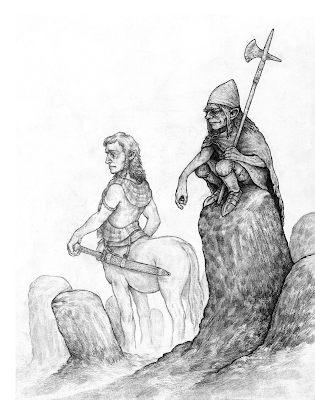

The Great North - Visual Delights

In the background, quietly, as my Yoon-Suin 2nd edition projects nears final fulfilment, work has been going on in relation to The Great North. Behold, some more glorious Tom Kilian art:

Not bad, eh?

.png)

.png)

%20Full.jpg)